There’s a joke in the creative industry that “everyone is a designer”, making light of how infuriating it is to have someone (without a visual background) tell a designer how things should look.

It’s a huge and common problem, caused by a “client is always right” attitude — something we’ve all experienced, and all must endure. There is a point where you can actually see the lights go off in a designer’s eyes as their soul tries to escape their body — and that point is usually the 10th round of amends.

Anyhoo.

Less talked about is the “everyone is a copywriter” problem. Today, we’re going to address that and dissect some of the things your copywriter is thinking when you decide that you’re also a midweight copywriter… but probably won’t say.

To your face.

Let’s not hesitate.

Grammar “rules” are guidelines, not rules.

This will split the sea like Moses, but let us go ahead and say it anyway.

Much like design, copy is subject to the tastes, preferences and aims of the reader. Every now and then, you (as the copywriter) will come up against a self-professed “grammar nazi”.

It could be your client. It could be your co-worker. Heck, it could even be legal. Sometimes they’re right, sometimes they’re wrong, but most of the time…

They’re an idiot.

You know how the saying goes that the ‘wisest people know that they in fact know nothing’? The same applies to grammar.

Language changes every year and in turn, so does grammar. The only time we ever really hear about it is when something controversial is added to the dictionary, like ‘lol’ or an alternative definition for ‘mug’… but it happens far more often than we realise.

There are often two (correct) spellings of every word and three (correct) executions of a punctuation rule. The rules change due to the rest of the words in a sentence, the academic style it’s written in, the context and even the medium. Therefore, unless someone has been studying the dictionary nightly since they were eight years old… the confidence of a grammar nazi is usually just drastically misplaced naivety, or the outward evidence of some deep-rooted childhood trauma. Whatever way you want to look at it. I’m not putting words in your mouth.

There are two types of grammar users.

The chances are, you (the copywriter) are a descriptivist grammar user and whoever is challenging you is a prescriptivist grammar user.

There is no reasoning with a prescriptivist. They’re lunatics.

Prescriptivist grammar users were not made for creative writing. They were born for legal and medical professions, where the grammar use is so intense that sentences no longer make sense whatsoever. Prescriptivist grammar users often desperately hang on to the “rules” taught to them in school till their dying day, killing any sense of fun or creativity by creating adverts that read like a terms and conditions section.

Descriptivist grammar users are generally the creative ones. They know the rules of grammar, but also how and when to play with them. They don’t particularly care when the rules are violated if it enhances understanding or clarity. As long as the message is communicated clearly (and doesn’t read like it was written by a child, your Mum trying to text, or someone who lurks in the Daily Mail comments section), then it’s good to go.

It’s down to preference, orthography, and communicating a tone of voice.

Creatives tend to be descriptivists by nature.

Have you ever noticed that the world’s favourite authors had different bad habits?

Virginia Woolf had a beautiful habit of swapping the narrative perspective mid paragraph. Jane Austen used double negatives. Charles Dickens was the king of run-on sentences — and E.E. Cummings didn’t give a flying cockatoo what you thought about capitalisation. That man capitalised whatever word he damned-well pleased. Or didn’t. Don’t get me started on Hemingway, whose grammar was a mix of playful creativity and 46% malt whisky.

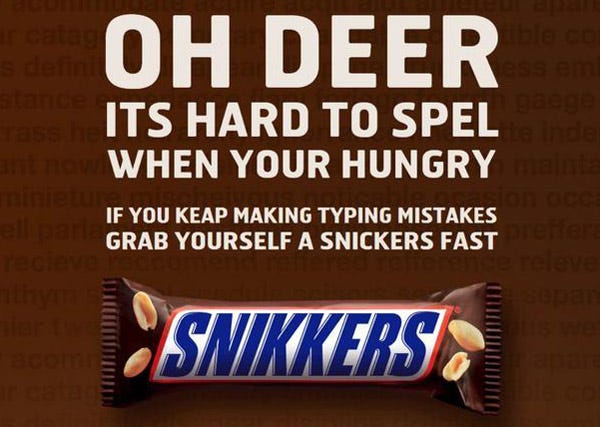

Like authors, creative copywriters have a license to do whatever the hell they want with grammar. They’re well within their rights to spell things wrong if it makes a point, abandon grammar altogether when necessary, and even make the grammar worse for the sake of a catchy line.

Let me explain with examples. Seasoned copywriters — you can skip this, you’ve heard it all before.

Apple’s “Think Different” should, by prescriptivist ruling, say: “Think Differently”… Yep, punchy.

If a prescriptivist had gotten hold of “Got Milk?” before it was published, it would read: “… Do You Have Any Milk?”

McDonald’s ‘I’m lovin’ it” should read: “I am loving it.”

Honda Civic’s “To each their own”?… To each his/her own.

But it doesn’t stop there.

It comes down to stupid stuff.

Each and every day, your copywriter will have to evaluate your full stops (or lack thereof). Your quotation marks (or lack thereof). Tone down someone’s excessive use of the exclamation mark. Prune unnecessary semi-colons from someone trying to look clever. Remove a misplaced ellipsis that has taken the headline from hilarious to cheesy in five seconds flat (or worse, borderline funny to outright creepy).

Everyone has a tone of voice, whether they realise it or not. Accents aren’t limited to the spoken word. Everyone has subtle habits, preferences and tendencies that they project onto the written word. It’s the copywriters job to wade through those tendencies and deem whether they’re acceptable or not. Happy-go-lucky types LOVE to add unnecessary exclamation marks! They do it naturally! Some People Genuinely Type In Title Case On Headlines For No Good Reason At All. Some love an unnecessary… ellipsis. Others have absolutely no idea where to close their sentences or when to shove a comma in believing the more flowery words they type the more it looks like they know what they’re talking about and these people even get copy bingo bonus points if they can do this with no commas but then achieve the holy grail at the very end; the unnecessary semi-colon.

Me? I like an unnecessary linebreak. What can I say? Flair for the dramatic.

Anyway, what this boils down to is that these tiny habits often end up on the first draft of an advert. It might be the copywriter’s habit, sometimes it’s the art director’s habit — and sometimes, it’s Jean from accounts, who has taken the opportunity to bollock up your advert because you were too sick to come into work and the artwork needs to go today.

Why does it matter?

Deep down in the pit of your stomach, when you’re looking at copy that isn’t ‘quite right’, you know. It’ll niggle at you. It should niggle at you. The use of punctuation changes the entire message you’re sending out — and copy is sales. You’re the salesman. It’s the difference between:

The best washing machine you’ve ever had…

The best washing machine you’ve ever had.

The best washing machine ever.

The best washing machine. Ever.

The best washing machine you’ve EVER had!

BEST. WASHING. MACHINE. EVER.

BEST washing machine you’ve EVER had!! buy now at a limited one-time-only price!!

WASHING MACHINES FOR SALE. CONTACT GARY 07384 77 77 77.

(Kidding.)

In terms of creative, sometimes a missing full stop on an advert is just a distraction. It doesn’t indicate a complete statement and the reader is left hanging on the edge, waiting for a punchline that never comes. Other times, the use of a full stop is the most distracting, out-of-place looking thing on the fucking planet and needs to leave the ad, pronto.

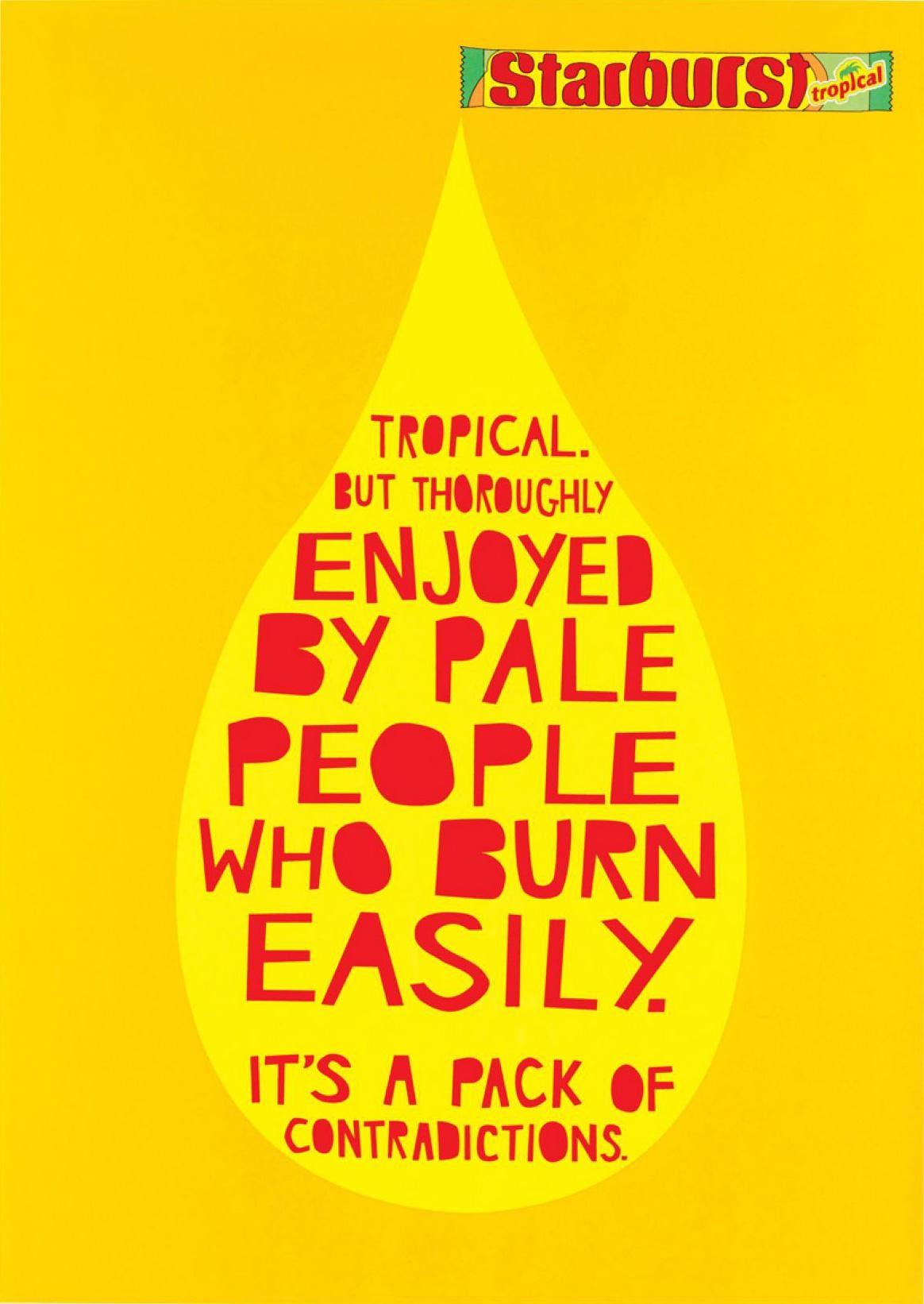

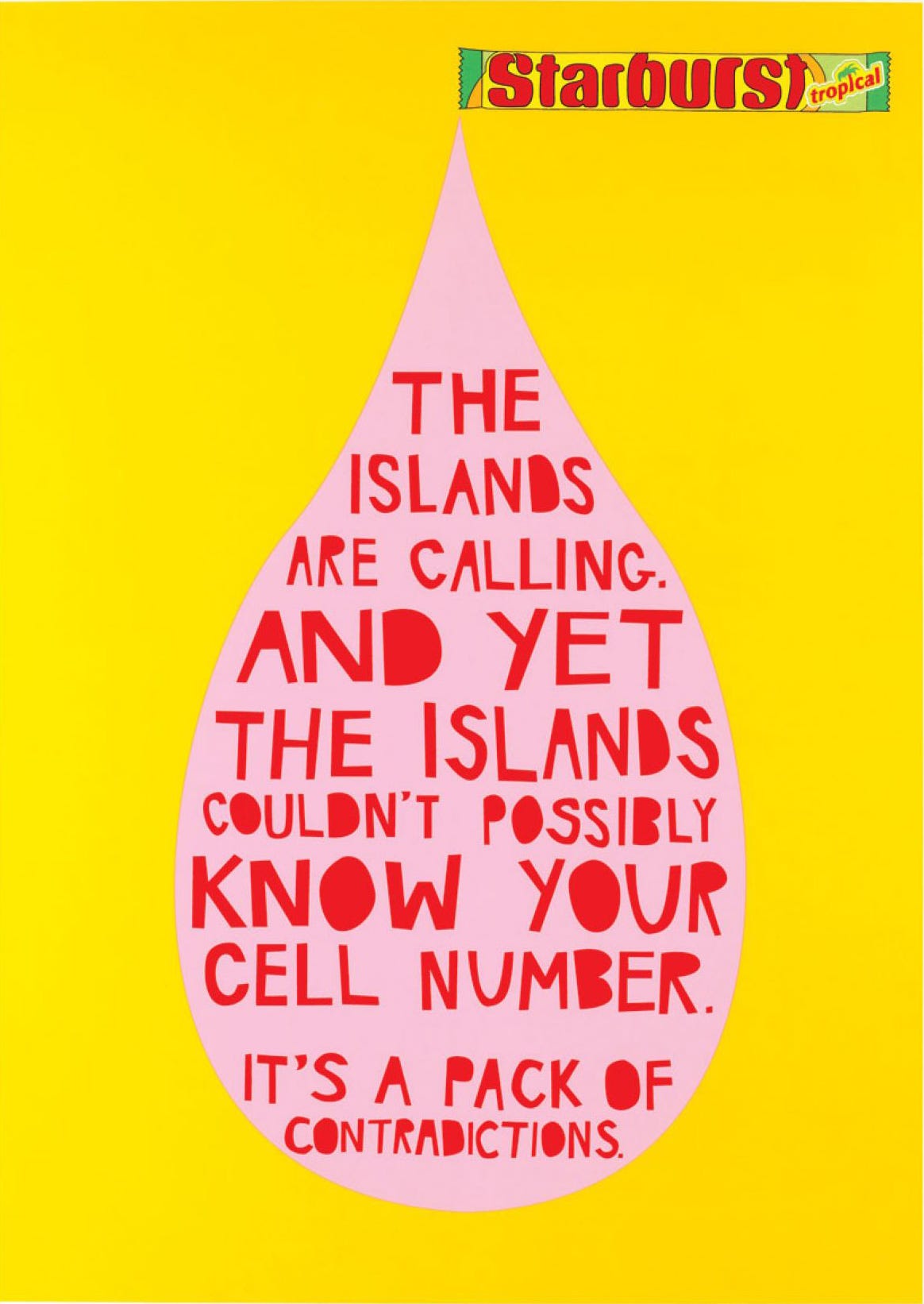

Here is a copy campaign from Starburst in 2011. Try reading it without full stops. Does it have the same impact?

“Should there really be a full stop after Tropical?” — Yes, Jean. You complete bore.

“Should there really be a full stop after Tropical?” — Yes, Jean. You complete bore.

This advert even starts a sentence with ‘and’. Prescriptivists will lose their damn minds.

This advert even starts a sentence with ‘and’. Prescriptivists will lose their damn minds.

Even removing one full stop on these adverts changes the tone of voice. It’s slight, but it’s important. The full stop gives your brain a break to evaluate the sentence you’ve just read, giving the joke further impact when you get to the punchline. And yet, before they were released, some prescriptivist jackass probably screwed up their nose and said “shouldn’t that all be one sentence?”… Jesus. Shut up Jean.

Copywriters will also come up against people who are the opposite of Jean. Some people just don’t believe in full stops. Usually the habit of vigilante ‘who reads the words anyway?’ designers, by the time the copy has been typeset — they’ve decided punctuation is irrelevant and removed all of it. It now reads like a child wrote it, or a lunatic.

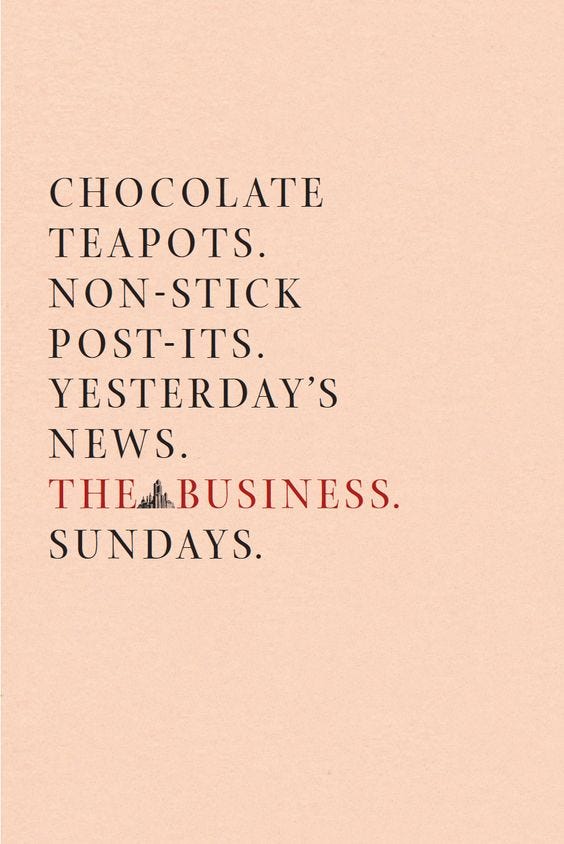

The below advert is pretty suave. It’s dressed up in a suit, it orders a flat white and it’s probably wearing an expensive watch.

Now, imagine removing all the full stops from it. That suave voice suddenly sounds like drug-fuelled gibberish, spouted at you from someone uncouth at a bus-stop: “CHOCOLATE TEAPOTS NON-STICK POST-ITS YESTERDAYS NEWS!”

And yet, it happens.

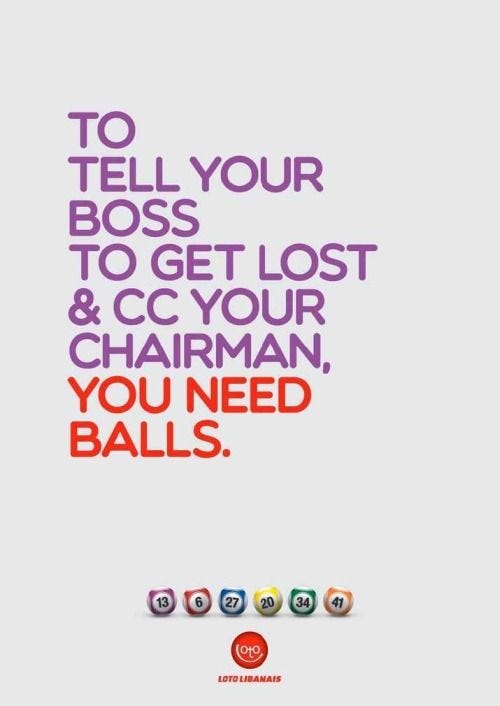

Here are some more examples, except this time, you’ll notice that basic grammar rules have been ignored altogether, for the sake of impact or tone of voice.

Unlike the above examples — where a prescriptivist lunatic or an anti-punctuation vigilante is making your day much longer and harder than it needs to be — these are conscious decisions from a copywriter and an art director. Be gone, pesky full stops! You’re useless to us now!

Many will assume that lowercase from innocent is just part of their font. Nope. They use capitals in their headlines too. Google it.

Many will assume that lowercase from innocent is just part of their font. Nope. They use capitals in their headlines too. Google it.

Brands aiming to appeal to parents often drop capitalisation and full stops altogether (innocent want to seem ‘innocent’). Equally, grammar is often abandoned for the sake of good execution (Heinz logo used as copy).

Other times? It’s just a cheeky act of rebellion used to enhance the tone of voice on ‘naughty’ adverts. See below.

“Should CC not have a colon after it? Should we not say copy in? Is the ampersand really necessary? Shouldn’t it start with you need balls to tell your boss to get lost and-” Shut. Up. Jean.

“Should CC not have a colon after it? Should we not say copy in? Is the ampersand really necessary? Shouldn’t it start with you need balls to tell your boss to get lost and-” Shut. Up. Jean.

Our job is to make sure that the voice matches the message. A copywriter will know the difference. An art director will know the difference. Jean, from accounts, will not know the difference — and there’s no point trying to explain it to her.

Another point to make here is that copy that has been written on a word document looks completely different to copy, typeset, on an advert. Your copywriter only knows what they’re really working with once they’ve seen the words applied to the creative. Full stops might have been included in the word doc they supplied, but once they see it on the advert… they’ll remove all of them. Equally, they might have removed all punctuation from the supplied copy, but once they’ve seen it on the design… put it all back on.

It’s not a mistake. It’s a judgement call.

Which leads me to my next point…

Copywriters can proofread, but they are not proofreaders.

They actually pay people for that, you know.

The glorious thing about being a visual creative is that you can fail your GCSE English and still be one of the most successful people in the country.

The slight downside is that most agencies must then rely on their copywriter to be both a creative and a pedantic proofreader… which makes it their job to try and wade through every teeny tiny bit of grammatical feckery that tries to escape the agency at large.

With that in mind, on any given day your copywriter is expected to pump out anything between 0–40,000 words (estimate, could be more).

Have you ever written 40,000 words in a day?

After word 35,587 — your eyesight has become a bit hazy, words have started to discombobulate on the screen, and you find yourself double-checking simple words you’ve known since you were six years old.

By word 40,151, the whole document could be littered with obvious typos… but for the lfie of you, by the tmie you get to that piont, you will no lnoger be able to see tehm.

The human brain does an unusual thing when we read our own words back (especially immediately after they’ve been written). Our brains subconsciously hop, skip and jump through the words (and grammar), as our verbal memory knows what is supposed to come next, and fills it in.

We may think we’ve read it, but like singing along to a song — our brains are filling in gaps, whether the words we think we’re reading are on the page or not. That’s why the general rule is that if you’re going to proofread your own stuff — it should be at least 24 hours after you wrote it.

Of course, in agency world, that’s a lovely fantasy but not at all realistic. Thus, when a typo does go through to design and it turns out it was — GASP — the Copywriter?!… You need to cut them a break.

And there you have it. Just a few of the reasons your copywriter gives you ‘that look’ when you try to mess around with the copy, write the copy yourself, or worse — request that they include five more sentences of benign waffle for legal reasons (that’s what the terms and conditions section is for — Damnit, JEAN.)

Go forth, armed with knowledge — and make your copywriter like you.

Amen.